Two rivers run through it

Whitewater rafting the Blackfoot and Clark Fork Rivers in Montana

Rafting Montana's Blackfoot River

I was probably underwater for only 45 seconds, but it felt like five minutes.

Partly this was because I was unable to breathe, and partly because I was unsure if the violently churning water would ever stop battering my body against the rocks and spit me out of the 18-foot-deep sinkhole at the bottom of Tumbleweed rapids.

And to think, Stew, Agnew, and I had imagined that three days floating the rivers of Montana would be a relaxing break from the physically taxing routine of hiking and camping our way across the continent as the adult leaders on Boy Scout Troop 116's cross-country summer odyssey.

Rolling down the Rivers

Our river guru, Dan Berger, was a former 116 member himself, now living in Missoula and working as a journalist and rafting guide for Montana River Guides (800-381-raft, www.montanariverguides.com; $45 for a half-day rafting trip, $74 for a full day).

For a scout troop on a tight budget, it was perfect: a rafting trip that cost us only for the food and rental of three duckies (inflatable kayaks) to supplement Dan's raft.

Rather than trying to find a new campsite each afternoon, we set up a base camp at the midpoint of our 20-mile float down the Blackfoot River. We could just paddle right in on the first day, out on the second, and not have to break camp until the third day in order to drive to another river—the Clark Fork of the Columbia—for some gnarlier rapids.

We loaded the six boys onto the raft with Dan while the three adults each took a duckie and circled the raft lazily as we floated down river. The Blackfoot was running fairly low, the rapids pretty tame, so Dan took the opportunity to drill the scouts in river rescue techniques and the esoterica of paddling.

Troop 116 spent much of its time rescuing men overboard and unwrapping itself from rocks.

By the end of the first day, he let the boys take turns at piloting the raft, which meant it suddenly began doing a lot more needless tacking back and forth across the river and beaching itself on barely submerged rocks.

For two days, the Blackfoot meandered past the tree-lined shores of Montana ranchland. Cattle loafed by the waterside. A doe lead her speckled fawn along the bank and watched us suspiciously.

Mud swallows skimmed the water scooping up insects, families of ducks left Vs in the water as they fled our odd craft, and a giant falcon swooped from the fir trees as if it to snatch Stew's hat off his head.

Near the end of the first day, a bald eagle kept pace with us for a while before wheeling off above the towering lodgepole pines.

Tumblereid

On the third day we switched to the Clark Fork and the rapids got serious. After a morning paddling with sore muscles through more technical stretches of whitewater and a game of water football at the edge of the gravely beach where we lunched, Dan told us it was time to exchange our floppy hats for helmets as there was a Class III+ rapid up ahead.

At Tumbleweed, the entirety of the river—some 2,000 cubic feet per second—coursed through a narrow gap in the rocks above what had to be an eight-foot drop. Dan piloted the raft up onto the crest of the high lateral wave that rose like a wall at the edge of the rapid then corkscrewed down into the trough on the other side.

The boys learn river rescue techniques by purposefully flipping their raft, then learning to right it again in the rapids.

The boys learn river rescue techniques by purposefully flipping their raft, then learning to right it again in the rapids.

Choosing discretion over valor, I let Stew and Agnew tackle it first.

That lateral wave grabbed Stew practically before he got into the slot, flipped him out of his duckie, and sucked him straight down into the hole of raging water below.

Agnew rode the wave for a split second longer before it tossed him, too, out of his little boat like a rag doll.

I adjusted my angle of attack and cruised up over the massive lateral wave without incident... only to be totally crushed by a second, even larger wave beyond it.

After 45 battered, slightly panicky seconds, the river finally did spit me out and spun me into an eddy along the cliff. Although my duckie had floated on down river without me (to be recovered—along with Stew, Agnew, and Agnew's duckie—by the guys in the raft), I had somehow managed to find my paddle.

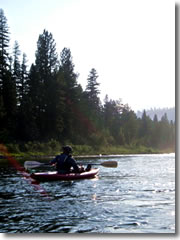

Dan Berger takes a moment to relax and paddle a duckie.

Luckily, Stew's duckie was caught in a neighboring eddy, so I was able to commandeer it and paddle, shakily but triumphantly, through the last of the rapids to the waiting raft.

Dan offered us the chance to climb aboard and not worry about anything beyond paddling for a while, but all three of us chose to stick to our duckies.

I even got my nerve back by the day's final stretch of whitewater.

Paddling furiously into the center breaks of the biggest waves, I rode the rapids with an added edge-of-danger thrill, for now I understood that the river had far more control over my fate than my meager kayaking skills ever did.

Related Articles |

|

This article was by Reid Bramblett and last updated in June 2012.

All information was accurate at the time.

Copyright © 1998–2013 by Reid Bramblett. Author: Reid Bramblett.