Trinity College

Ireland's most famous university is home to the world's most famous medieval illuminated manuscript: the Book of Kells

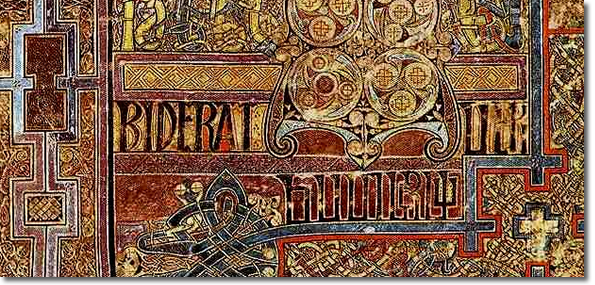

A detail from the Book of Kells at Trinity College (Folio 292r, Incipit to John, In principio erat verbum)

A detail from the Book of Kells at Trinity College (Folio 292r, Incipit to John, In principio erat verbum)

In the middle of Dublin city is an oasis of peace, green, 18th- and 19th-century buildings, and students scurrying with their books.

A bit of Trinity College history

The Campanile seperating paved Parliament Square from grassy Library Square at the entrence to Trinity College, Dublin. Queen Elizabeth I founded Trinity College in 1592 to enlighten and educate the Irish—or, as the English monarch herself put it rather more blunty, to "reform...the barbarism of this rude people."

Trinity, in the end, turned out to be more enlightened than its English counterparts at Cambridge and Oxford, being the first of the three to admit women (in 1903).

Among Trinity's 92,000+ alumni are counted such illustrious graduates as Jonathan Swift, Thomas Moore, Oscar Wilde, Bram Stoker, and Samuel Beckett—so you never know who that undergrad giving you the €5 tour might grow up to be. (You can tell he’s an undergrad because his knee-length robe lacks the sleeves that are accorded only to grad students, so it’s more of a cape-vest.)

The modern Trinity College Dubin matriculates around 16,800 students each year, and is currently ranked 61 in the Top 100 colleges in the world by the QS World University Rankings.

Incidentally, among the other benefits accrued to those lucky few Trinity collegians who achieve the top mark on the rigorous, voluntary Foundation Scholar exam—including free room and board for 15 terms (that’s five full years), a stipend, and the right to append “Sch.” to their names—is the right to unlimited half-pints of Guinness at meals. Sweet deal—though there are only 70 Scholars at a time.

Trinity College tours

A tour of Trinity College with a student. The entertaining student-led tours provide plenty of fun anecdotes about the university's history, student life across the eras, and odd traditions, along with a bit of commentary on the architecture (and the juxtaposition of venerable older buildings with varyingly successful forays into modernist architecture).

These tours end at (but do not enter) the most famous and popular bit of Trinity, the Old Library and its exhibiton on the Book of Kells.

Trinity's Old Library & the Book of Kells

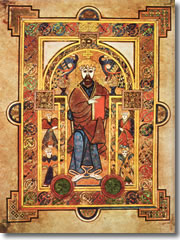

A page from the Book of Kells (Christ Enthroned, Folio Most visitors head straight for the Old Library, built in 1712, where there is a fine display on the medieval art of manuscript illumination—a craft at which the Irish excelled.

The library is home to a precious trinity of illuminated manuscripts: The 7th century Book of Durrow, the 8th century Book of Armagh, and Ireland's most richly decorated treasure, the 9th-century Book of Kells.

Stolen from its monastery in 1007 by Viking raiders, the Book of Kells was miraculously recovered from a bog three months later. Its gold-rich cover was missing, but the experience did little harm to the vibrant colors and remarkable detail in what is perhaps the most beautiful, important, and cherished illuminated manuscript in the world.

A detail from the famous Chi Rho page of the Book of Kells (Folio 34 recto) The Book of Kells is actually four books (one for each Gospel), and two are on display at any given time, one turned to an illuminated page, the other to a page of text. The interpretive museum you file through before arriving at the chamber housing the trio of illuminated manuscripts fills you on the art of illuniation and the history of the Book of Kells and other old books in the library's collection.

The museum also cleverly uses projectors to turn the first wall on your right as you enter into a daily changing exhibit on whatever page the Book of Kells happens to be open to that day, detailing the drawing that is on display and explaining some of its iconography.

Somewhere around the year AD 800, a collection of Irish Columban monks were laboring over 340 folios of fine, calf-skin vellum in the scriptorium of their monastery on the windswept island of Iona just north of Ireland, off the coast of Scotland’s Isle of Mull.

They were faithfully copying out the Vulgate Latin text of the Four Gospels in iron gall ink, the lasting acidic tint favored by everyone from Pliny the Elder, penning his eyewitness account of the destruction of Pompeii, to scribe Timothy Matlack in 1776 setting to parchment the words of Thomas Jefferson, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal...”

But the Iona monks didn’t just work in ink. Like other Anglo-Celtic monks of the period, they also mixed pigments—the reds and yellows of crushed ochre, the deep purples of the indigo plant, green verdigris from copper, intense ultramarine from lapis lazuli—to surrounded these sacred words with a colorful riot of impossibly delicate illustration, mixing early Christian iconography with Celtic motifs and patterns, portraits of saints with depictions of mythological monsters.

But real monsters were at the door: Viking raiders.

The Vikings began their ambitious campaign of sacking, pillaging, and eventually settling the lands surrounding the North Sea (as well as Russia, Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland—which today we call Newfoundland and Labrador in Canada) with the British Isles.

The first Viking raid was on the island monastery of Lindisfarne off the northeast coast of England—the only real rival to Iona for the painterly skills of its monks. It was an ideal score: Plenty of gold and silver reliquaries and other church riches guarded only by a bunch of scholarly monks. (Thankfully, the Vikings didn’t bother with Lindisfarne’s illuminated manuscripts, which are now at the British Library.)

They casually slaughtered many of the brothers, carried other off as slaves, and started plotting their next raid.

Within a year, in 794, they hit Iona for the first time, giving those monks the same Lindisfarne treatment. The remaining brothers, shaken, carried on with their devotions and their work, perhaps even redoubling their efforts at their collective masterpiece in the scriptorium.

But in 806, a particularly brutal Viking raid left 68 of the monks dead, and most of the survivors dispersed. Some fled south to a brother monastery in the Kingdom of Meath in Ireland called Kells, bringing the Book with them and continuing their laborious illustrations.

By no means did this keep the monks—or their Book—safe. Vikings raided inland as well, hitting Kells numerous times throughout the tenth century. Nor was the Book safe from local thieves.

In fact, the earliest direct reference to the Book comes from 1007 in the Annals of Ulster—which is notable in of itself, as about 99% of the entries in these records consist only of brief notations about battles or the deaths of kings, chiefs, abbots, and other notables—in which it was recorded that the Book—which it calls “...the most precious object of the western world on account of the human ornamentation...“—was “...wickedly stolen by night from the western sacristy…”

Luckily, it appears the thieves were only after the same kind of worldly wealth as Vikings. Two months and twenty days later, the book—minus its gold-bedecked cover—was recovered from “under a sod.”

But somehow, the Book of Kells survived.

Because it’s Irish. The Irish are survivors.

The Long Room

The Long Room in the Old Library at Trinity College, Dublin Upstairs from the chamber with the Book of Kells is the Old Library's bust-lined Long Room, the aptly-named main stacks of the original library, a 65-meter (213-foot) built in 1712–32 (the second level was added in 1860) and housing 200,000 books alongside busts of famous writers, philosophers, and others associated with Trinity.

Ancient, leather-bound tomes are arranged according to an idiosyncratic, pre-Dewey Decimal filing system in tall nooks on either side of a two-story hall, reached by rickety wooden ladders on runners.

(If it all looks vaguely familiar, this may be because George Lucas copied the look for the Jedi Library in Star Wars: Attack of the Clones.)

The Old Library is, ironically, on one of the modern modern quads at Trinity College.Down the center of the hall are display cases showcasing some of the library's collections, usually along some theme (on my last visit, I got to see old medical texts and instruments—as fascinating as they were gruesome).

Also on display here is the harp of Brian Ború, more than 600 years old and one of only three wooden Gaelic harps in existence. Legend holds it to be the one played during Brian Ború's Battle of Clontarf—though that happend in 1014, and the harp likely only dates to the late Middle Ages.

Its profile is familiar to anyone who has seen the official state heraldry of Ireland, the backs of their Euro coins, or a pint of Guinness.

Fellows Square and the Berkley Library

Incidentally, the Trinity library actually has many branches and buildings.

The largest section, is housed, in part, on the college’s Fellows Square, where only university fellows are allowed to walk on—and, according to the school charter, graze their sheep on—the grass.

This bit of the library—in a neo-Brutalist monstrosity the students have dubbed “The Photocopier”—is named for the early 18th century Anglo-Irish philosopher and Trinity grad George Berkeley (pronounced "Barclay" in Irish), who had also lived in Newport, RI, for a spell, where you can visit his Whitehall mansion, and ended up the namesake for a college at the University of California—though we Yanks mangled the pronunciation of his name and rendered it phonetically as “Berkeley.”

Tips

- Planning your time at Trinity College: Give the Old Library and the Book of Kells at least 30 minutes—but budget another 15–20 minutes for standing in line to get tickets. When it's crowded, guards move visitors through the book chamber every two minutes, so you might only get the briefest glimpse. Solution: Arrive when it opens, dash through to see the Book, then backtrack to tour the museum bit before heading upstairs to the Long Hall.

Student-led campus tours take 30 minutes—and get you a ticket to see the Book that lets you bypass the ticketing desk and long line (though you'd still have to wait in that line if you want to rent an audio guide to the Book of Kells exhibit). - Student-led tours of Trinity College: Take one of the 30-minute, highly informative and fun student-led tours of campus that leave from the Front Arch of the college (just inside the College Green entrance). They cost €5 (or €10 to get a Book of Kells entry as well) and leave at 10:15am, 10:40am, 11:05am, 11:35am, 12:10pm, 2:15pm, 3pm, amd 3:40pm (no 3:40pm tour on Sundays). Tours run mid-May through September (as well as on some weekends during term).

Hint: Most people believe the early bird gets the worm and therefore arrive for the first tour of the day—but in this case the early bird only gets a huge crowd of 70 to 120 people. Show up for the second tour at 10:40am (or any later tour) and the crowds are 1/5 that size or less. - Commercial tours that visit Trinity College: Take a tour that includes a stop at Trinity College with our partners at Viator.com:

Related Articles |

Related Partners

|

This article was by Reid Bramblett and last updated in February 2012.

All information was accurate at the time.

Copyright © 1998–2013 by Reid Bramblett. Author: Reid Bramblett.

College Green (enter where Dame St. runs into Grafton St.)

Tel. +353-(0)1/896-2320

www.tcd.ie

OPEN

Old Library : Mon–Sat 9:30am–5pm, Sun 9:30am–4:30pm (Oct–Apr, doesn't open Sundays until noon).

ADMISSION

College: Free

Book of Kells exhibit: €9

Tours: €5 (or pay €10 and get in to see the Book of Kells as well—a bargain)

TRANSPORT

Bus: 7N, 15N, 15X, 44N, 46N, 48N, 49N, 50, 51D, 51X, 54N, 56A, 77A, 77N, 79B, 70X, 92

DART: Pearse St. or Tara St.

LUAS: Abbey Street or St. Stephen's Green