St. Peter's is one of the holiest basilicas in the Catholic faith, the pulpit for a parish priest we call the pope, one of the grandest creations of Rome's Renaissance and baroque eras, and the largest church in Europe.

(It was biggest church in the world until an ugly barn of a place was recently completed in Africa.)

You approach the church through the embracing arms of Bernini's oval colonnade, arranged in four rows and topped with 96 statues of saints, which encompasses Piazza San Pietro.

Actually, this "oval" is a perfect ellipse—and I can prove it.

Bernini's engineering was spot-on. You can even see his perfect perspective trick if you stand in the proper spot.

Find one of this oval piazza's foci, marked by round marble plaques set into the ground between the central ancient Egyptian obelisk and the flanking fountains to either side.

Keep an eye on the nearest colonnade as you approach the focus. When you reach the marble disc, the four-deep rows of columns of that colonnade will line up perfectly and suddenly appear to consists of only a single, curving row.

Neat.

The church itself takes at least an hour to see—not because they are too many specific sights; it just takes that long to walk down to one end of it and back.

St. Peter's sheer dimensions are staggering: 614 feet long, 145 feet high in the aisle soaring to 385 feet inside Michelangelo's dome (which is itself 137 feet across).

Mocking bronze plaques set in the floor of the central nave mark just how short the world's other great cathedrals come up.

However, since everything is done to scale, its immensise size is not always immediately apparent. I mean, it certainly looks big, but not mind-boggling big.

Look more closely, though.

Fun fact

St. Peter's is not the cathedral of Rome. The pope's true title is Bishop of Rome, and as such his official home church—and Rome's cathedral—is actually San Giovanni in Laterano.

First of all, notice the people milling around the baldacchino, that fancy twisty-clumned canopy over the main altar. Notice how they look like ants? Guess what? They're still only about two-thirds of the way to the other end of the basilica.

Here's an even better measuring stick. Check out those cherubs frolicking around the bathtub-sized holy water stoups. They really do appear to be baby-sized—until you get up close to them and realize they would be around six feet tall if they were standing next to you.

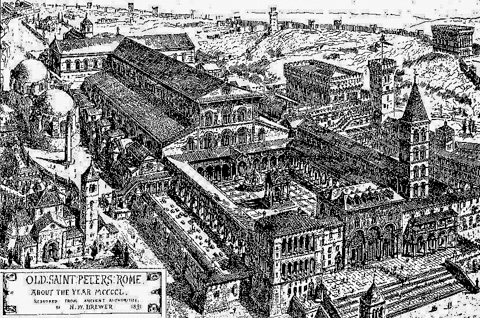

The most magnificent basilica on Earth is a late Renaissance/early baroque masterpiece of architecture and decoration. St. Peter's was worked on by just about every great architect and artist of Italy's 16th and 17th centuries: Bramante, Raphael, Peruzzi, Antonio Sangallo the Younger, Michelangelo, Maderno, and Bernini.

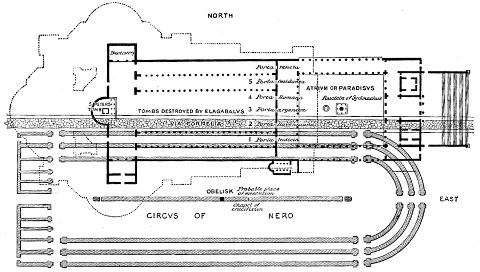

There has been a St. Peter's church on this site since the 4th century, when early Christians rasied a chapel near the supposed spot where St. Peter himself was buried, reportedly behind a red wall—very close to the site where he was martyred, in the Circus of Nero, the foundations of which lie under the church to this day. The chapel was expanded over the years to become the original, medieval Basilica of St. Peter's.

By the late 1400s, this medieval basilica was beginning to crumble, so the Vatican decided to erect a new structure worthy of the new Renaissance architectural style just beginning to flourish.

This Renaissance version of the basilica went through many architects, each attempting to realize a personal vision.

It was started by Bramante in 1506 (on a Greek Cross floor plan), continued by Raphael (who chose to adapt it to a Latin Cross plan), then by Peruzzi (back to Greek Cross), and Antonio Sangallo the Younger (Latin Cross again).

Of course, the popes just had to involve Michelangelo, and he decided—surprise!—to switch back, once again, to a Greek Cross again. The major contribution Micheangelo made that remains today was raising the dome—still the tallest in the world.

Finally, Giacomo della Porta and Carlo Fontana completed it in 1590 more or less in line with Michelangelo's designs,

Then in 1605, they tore down the facade and brought in Carlo Maderno who—tell me you didn't see this coming—lengthened the nave so as to finish it off in a Latin Cross plan by 1626.

For a final, baroque flourish, Bernini—in addition to creating the piazza out front—took care of much of the interior decor from 1629 through the 1650s.

Admire Michelangelo's youthful masterpiece Pietà in the first chapel on the right, sculpted at the age of 25.

The beauty and unearthly grace of sweet-faced Mary and her dead son, Jesus, led some critics of the day to claim the 25-year-old Florentine sculptor could never have carved such a work himself.

An indignant Michelangelo returned to the statue and did something he never did before or after: He signed it, chiseling his name unmistakably right across the Virgin's sash.

Notice how some of the details seem exactingly perfect and yet are exaggerated for effect. For example, the Virgin's lap is mountainously large in order to support the body of a full-grown man without seeming unbelievable.

The Pietà has been behind bulletproof since 1972 when a crazed geologist attacked it with a hammer, hacking off Mary's nose and fingers (since repaired) while screaming, "I am Jesus Christ!"

If the Cappella di San Sebastiano—one chapel up from the Pietà—looks a little busy, it is because the remains of the newly-minted St. John Paul II are buried directly underneath. (You can see the former pope's actual tomb in the Papal Crypt.)

At the end of the left asile, the first major pier supporintg the dome serves as a backdrop for a late 13th century bronze statue St. Peter by Arnolfo di Cambio.

This architect of Florence's Gothic palazzi was also an underrated sculptor, and his greatest work in Rome does double duty as a piece of art and a holy good luck talisman for the faithful—you'll often see a line of people sidling up to touch or kiss his outstretched foot, by now worn to a shiny nub.

The four great piers that support the dome each preserve a major-league holy relic—the statues in the 30-foot-high niches give you clue as to what relic is in each:

Stand under the 96-foot-high baroque confectioner's-piece baldacchino (altar canopy) with its twisting columns cast by Bernini in 1524 using bronze revetments removed from the Pantheon. St. Peter's tomb is directly beneath it.

Behind the altar, against the back wall of the apse, is a massive confecionary of gold and bronze and filtered sunlight called the Cathedra Petri, the Throne of Peter. Encased at the center of the great bronze throne is the simple wooden seat said to have been used by St. Peter hismelf—and subsequent popes for 16 centuries—as his cathedra, or bishop's chair. (A somewhat more believable chruch tradition states that it was a a gift from Charles the Bold to Pope John VIII in 875. Other analysis actually dates it closer to the 12th century.)

Chigi Pope Alexander VII decided to retire the deteriorating relic and had Bernini whip up this overwrought setting for it, a mountain of gilded bronze rising to the Gloria, a river of gold and cherubs flowing from golden sunrays emanating from a series of yellow alabaster discs, shaved thin to let through the natural sunlight and set with a single dove of the Holy Spirit at its center.

It's impressive, but all a bit much.

Much cooler is the nearby tomb for Pope Alexander VII, also by Bernini, with the pious pope kneeling hands folded and gazed at adoringly by the Virtues he most embodied (Truth, Charity, Prudence, and Justice), atop a green marble pedestal that rests atop hillock of folded red jaspar drapery... from which is emerging a golded bronze skeleton holding aloft an hourglass.

This is called a memento mori, Latin for: "Remember: You, too, will die"—and is meant to remind popes and other wordly hot-shots to be humble, but really just comes off as part creepy, part wicked-cool.

Top billing in its collections goes to a marble ciborium carved by Donatello, and the enormous bronze slab tomb of Pope Sixtus IV, cast by early Renaissance master Antonio del Pollaiuolo in 1493.

it's a true Humanist-era work, marrying sacred and secular aspirations. Around its edges are relief panels personifying the seven virtues—Faith, Prudence, etc.—and others depicting scholarly disciplines—Astrology, Grammar, Rhetoric, Dialectic, Music, Geometry, Arithmetic, Philosophy, Theology, and Perspective.

Note that there are two burial areas underneath San Pietro, and many people get them confused. The only one you can get into from the church itself on a regular admission is the Papal Crypt, or Vatican Grottoes. (The other—the more ancient Scavi di San Pietro necropolis with St. Peter's Red Wall—is only accesible on speical, booked-ahead guided tours.)

Anyone who shows up at the pier to the right of and behind the main altar can walk down a short staircase into the first burial level, usually called the crypt or "Vatican Grottoes." (Note: sometimes they use the entrance by the rear left pier.)

In the low-ceilinged space, art fans get to see 15th-century bronze plaques on the lives of Sts. Peter and Paul by Antonio del Pollaiuolo and remaining bits of Constantine’s original basilica.

But the star attractions are the tomb chapels of some 91 popes—including St. John Paul II. However, there are a few tombs here that are not those of popes—and are a bit surprising. In the Vatican crypt rest in peace the remains of some rather famous exlied European royalty.

Queen Christina of Sweden renounced her throne so she could convert to Catholicism and lived out much of her life here in Rome (in the Palazzo Corsini).

There are also the simple tombs of the would-be Jacobite kings, James Francis Edward, Prince of Wales—"The Old Pretender," son of the deposed King James II of England/James VII of Scotland—and his sons, Bonnie Prince Charlie (more formally: Charles Edward Louis John Casimir Sylvester Severino Maria Stuart), and Henry Benedict Stuart.

Visiting the crypt is free, but it's also a one-way experience—you end up exiting into a narrow space between the basilica and Vatican walls where your only choices are to get in line to get up the dome (see below) or head back out into the piazza, so save the crypt for when you're done with the interior of St Peter's.

Note that the Tombs of the Popes close one hour before the St. Peter's itself.

» Note: These are not the famous Scavi di San Pietro sub-crypt, the "St. Peter's Excavations" that unearthed an ancient necropolis directly beneath the basilica—supposedly containing the "Red Wall" behind which St. Peter's bones were buried—which you can visit only by a guided tour arranged well ahead of time. » more

You must pay to take the elevator then climb (320 steps) to the top of St. Peter's dome—but it's worth it. (You can save a couple of euros by opting to climb the entire way: 551 stairs.)

Michelangelo himself designed this dome to loft 135m (450 ft.) above the ground at its top and stretch 42m (139 ft.) in diameter.

In deference to the Pantheon, Michelangelo made his dome 1.5m (5 ft.) shorter across, saying "I could build one bigger, but not more beautiful, than that of the Pantheon."

Carlo Maderno later added the dome-top lantern, which today affords visitors a fantastic and dizzying city panorama.

Piazza S. Pietro

tel. +39-06-6988-3731 or +39-06-6988-3712

www.vatican.va

Church: Daily 7am–7pm (to 6:30pm Oct–Mar)

CLOSED WEDNESDAY MORNINGS if there is a papal audience in the piazza; it reopens when the audience is over, around 1pm.

Cupola/roof: Daily 8am-6pm (to 5pm Oct–Mar)

Necropolis: By reserved ticket only; see below

Church: free

Dome: €7

Necropolis: €12

Roma Pass: No

Bus: Take the 40 or 62 (or 23, 34, 271, 982, 280, or N11) to Piazza Pia, then loop bus 62; full details under "How to get to St. Peter's" in Tips). Also stopping nearish St. Peter's: 116, 116T, Tram 19, 32, 46, 46B, 49, 81, 98, 492, 571, 590, 881, 916, 916F, 982, 990, N5, N15, N20

Metro: Ottaviano-S. Pietro (A)

Hop-on/hop-off: Vaticano

Planning your day: St. Peter's can be done in 45 minutes at a trot, but expect to spend more like an hour in just the church, 2–3 hours if you do all the extra bits (into the museum, down to see the tombs, and up onto the roof).

That said, expect to spend all day seeing this and the nearby Vatican Museums, even on a tight schedule. Don't worry; they're worth it.

St. Peter's has a strict dress code: no shorts, no skirts above the knee, and no bare shoulders. I am not kidding.

They will not let you in if you do not come dressed appropriately. Again, I am not kidding.

If it is a hot day and you want to walk around the city in a tank top and/or shorts, just pack and carry a light shawl to cover up when you get to St. Peter's (and other churches).

If you roget—or in a pinch—guys and gals alike can buy a big, cheap scarf from a nearby souvenir stand and wrap it around legs as a long skirt or throw over shoulders as a shawl.

They no longer allow you to take large bags or purses into the basilica.

Luckily, they've also arranged a drop-off point for all bags in a room just to the right of the steps leading up into the church.

This service is free.

There are free guided visits to St. Peter's run by volunteer professors and scholars from North American College in Rome.

They're offered Mon–Fri at 2:15pm and 3pm, Sat at 10:15am and 2:15pm, and Sun at 2:30pm.

They meet in front of the Vatican tourist info office, which is to the building along Piazza S. Pietro just left (south) of the main steps into the basilica.

Take a guided tour of St. Peter's Basilica with one of our partners:

Ottaviano-San Pietro is the closest Metro stop (on the A line, about nine blocks to the north at the intersection of Viale Giulio Cesare and Via Barletta/Via Ottaviano).

You used to be able to take famed bus 64 ("The Pickpocket Express") straight from Termini train station to St. Peter's. However, a few years back the bus authority decided, in its infinite idiocy, to truncate this useful line and force everyone to switch buses just seven (long) blocks from their goal.

Now, you can only take the 64 (or its faster, express cousin the 40, as well as neighborhod buses 23, 34, 271, 982, 280, and N11) as far as Piazza Pia (next to Castel Sant'Angelo).

From Piazza Pia, you can either walk (seven boring blocks down the stark, shade-free, Fascist-era Via della Conciliazione boulevard) or transfer to bus 62, the St. Peter's shuttle, which trundles in a short loop to a stop just outside the Vatican walls off the NE corner of the Piazza San Pietro colonnade. (One redeeming feature of this bus: For part of its run it follows Borgo S. Angelo/Via dei Corridori alongside the famous passetto, the wall-top brick viaduct the Pope can use as a personal escape route to Castel Sant'Angelo.)

You can attend services at St Peter's Monday to Saturdays at 8:30am (in the Cappella del Sacramento), 9am, 10am, 11am, and noon (all at the altar of San Giuseppe), and 5pm (at the high altar).

Sunday mass in St. Peter's is held at the high altar at 9am, 10:30am, 11:30am (in the Cappella del Sacramento), 12:15pm, 1pm (at the altar of San Giuseppe), and 4pm.

There is also often a 5pm Vespers on Sundays.

For the liturgical calendar listing when the Pope himself says mass, check out www.vatican.va.

For more on Papal Audiences of all sorts, click here. » more

Share this page

Search ReidsItaly.com

Piazza S. Pietro

tel. +39-06-6988-3731 or +39-06-6988-3712

www.vatican.va

Church: Daily 7am–7pm (to 6:30pm Oct–Mar)

CLOSED WEDNESDAY MORNINGS if there is a papal audience in the piazza; it reopens when the audience is over, around 1pm.

Cupola/roof: Daily 8am-6pm (to 5pm Oct–Mar)

Necropolis: By reserved ticket only; see below

Church: Free

Dome: €7

Necropolis: €12

Roma Pass: No

Bus: Take the 40 or 62 (or 23, 34, 271, 982, 280, or N11) to Piazza Pia, then loop bus 62; full details under "How to get to St. Peter's" in Tips). Also stopping nearish St. Peter's: 116, 116T, Tram 19, 32, 46, 46B, 49, 81, 98, 492, 571, 590, 881, 916, 916F, 982, 990, N5, N15, N20

Metro: Ottaviano-S. Pietro (A)

Hop-on/hop-off: Vaticano