- Places

- Plans

- Itineraries

- Experiences

Left: A mosaic griffin from the cathedral in Bitonto, Apulia. Right: A mosaic sphinx from the cathedral in Otranto, Apulia.

You will see a lot of mythological and fantastical creatures in Italian churches, particularly in the mosaics and carvings (around doorways and on column captirals) of the Romanesque period. (My favorites are in Apulia.)

Why all the monsters?

Well, some were just fantastical fun for the artisans and for the (largely) illiterate churchgoers to stare at during those long sermons in Latin.

But most actually had a specific meaning in medieval iconography.

The church co-opted many mythical (and some real-yet-fabulous) beasts and grafted on their own subtle and complex meanings.

Let's highlight two in particular, because the pay-off is so much fun.

You will often see griffins on medeival churches—not because medieval churchmen were big into D&D-style role playing games and fantasy novels, but because the beast's dual nature—head of an eagle, body of a lion—symbolozed the duality of Christ—the god-made-flesh mortal man (the Lion of Judah) and the heavenly father (angelic wings and whatnot).

So, what's with the sphinxes you'll also sometimes see?

The Evanglical tetramorph.Well, you can read the sphinx as a kind of human-headed griffin...

Or you can tease those four totemic animals apart a bit and read it as a quartet of divinely-inspired humans bearing witness to the Gospel.

After all, a sphinx has the head of a human, the body of a lion, the tail of an ox, and the wings of an eagle.

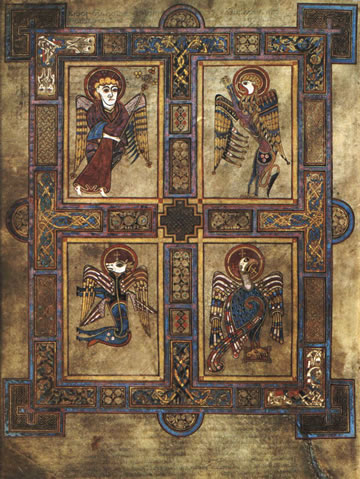

The Evangelists as they appear in the Book of Kells. Or, to put it another way, the traditional symbols of the Evangelists and authors of the New Testament:

An Assyrian lamassu griffin, now in the Louvre.Incidentally, this particular quartet of totemic animals was not original to the Christians, as anyone who has been to the Louvre, British Museum, or University of Chicago Oriental Institute can attest, having seen their majestic Assyrian Lamassus from the 8th century BC.

This monstrous mash-up of a totem even has a name: The tetramorph.

The tetramorph pulling the merkabah, in the vision of Ezekiel.The Christians inherited it by way of mystical Judasim and the Book of Ezekial (who was exiled to Assyria and so would have known all about the Lamassu), in which those four creatures pulled the Merkabah, or chariot of God.

(Getting back to Italy, this also explains why Venice has lions all over the place; it is the city of St. Mark.

Actually, Alexandria was the city of St. Mark, but Venice stole him. No really. They hid him in a barrel of pickled pork to smuggle him past the muslims. Seriously.)

Share this page

Search ReidsItaly.com